Soh Eugene: Unpretentious and bold hero behind the scene

“Sanjee, I am ready to go anytime. I have done my part, seen and lived the world. I’ve lived enough to see military in Korea sent back to their barracks [out of politics] for good. The greatest satisfaction is that I can die seeing a freer Korea, that if I wanted I can go to the street and shout out loud that the president is a son of bitch and I won’t get arrested and tortured for that. That is my happiness and I will go as a happy man.” – Soh Eugene

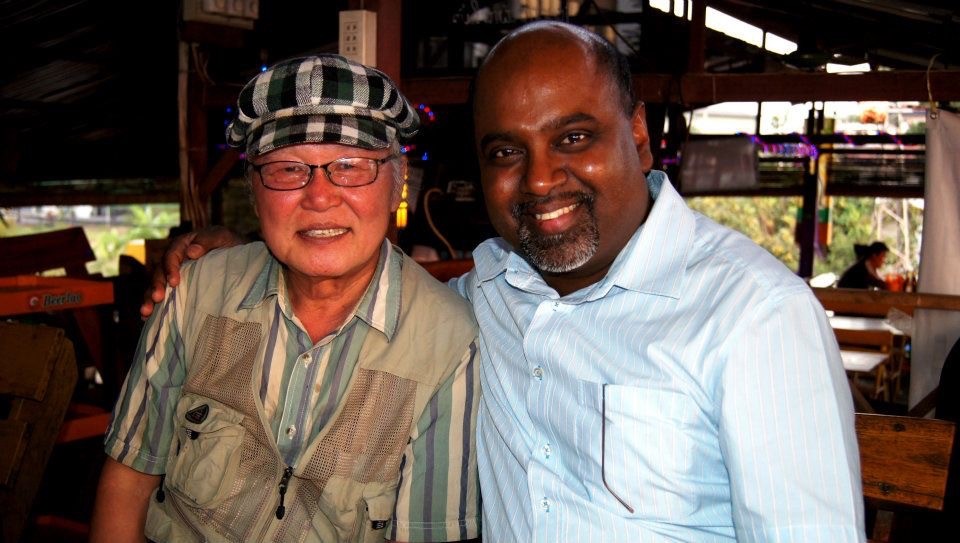

He told me this almost 5 years ago when I was visiting Phnom Penh, Cambodia. For those who are close to Eugene, these are familiar words. If I knew Eugene was around, I will always see him in Phnom Penh more than once. We ate and drank and talked about how bad the politics and politicians are in general and everywhere. Eugene was a friend, an elder and a wise man.

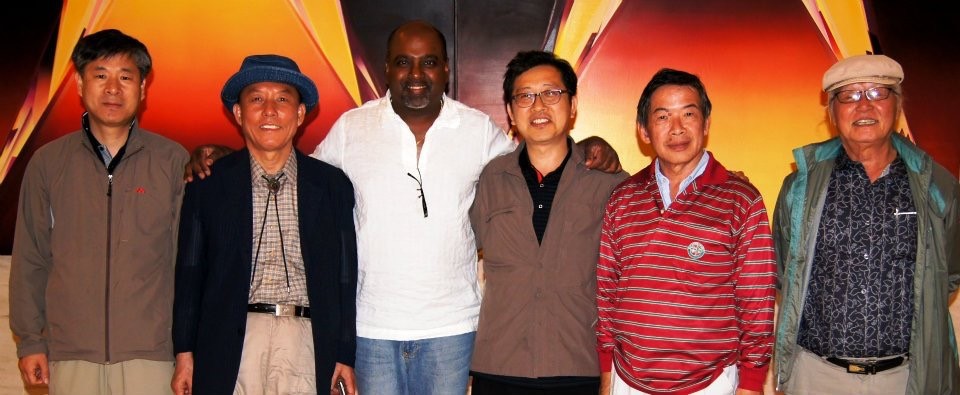

My first memory of Eugene Soh was in May 1996 in Kwangju when I first visited there. He wore a light blue business suit and kept sharing his critical analysis of the Korean political landscape. Kim Young-sam was the current president and Eugene spoke highly of him but criticized Kim Dae-jung for his shortcomings and political compromises (or DJ as he called him).

I did not know much about him then. He was a private man. But he cared about his close and trusted group of friends, whether they were local or foreign.

Eugene belonged the generation of student activists who inspired by the 4.19 April Revolution/movement when mass protests were held against (Korean: 4.19 혁명), from 11-26 April 1960. Soon after Korea came under the military dictatorship of Park Chung-hee. It was during this period that Eugene migrated to the US. He told me how difficult life was during his first years there. When people could not understand what he was saying, he was often insulted with words like “damn Chinaman, learn to speak properly.” He told me how his wife used to work carrying their baby son or daughter on her back late into the nights. He worked hard to establish himself in the US. But as a proud son of Cholla, he could not forget what was going in South Korea. He continued his activism in the US. He learned from other campaigns and from activists from Central and South American countries. He lobbied against congressmen and senators. He protested outside the Korean Embassy in Washington DC. He told me that he would often go out and shout at Korean diplomats who were serving the military regime at the time. One such diplomat was former Secretary General of the UN, Ban Ki-moon who was a counselor attached the South Korean Embassy. There was this one occasion when he had shouted at him “you son of a bitch, why are you serving a brutal military regime?” Ban Ki-moon later told privately to Eugene, “Mr Soh, please don’t shout in public like that.” Eugene’s reply was “I have nothing personal against you but your role. So, it is my duty to call you out in public for the regime you are representing.”

It was also during this time that Eugene was asked to accompany the late president Kim Dae-jung. Kim traveled to US after he was almost killed after being abducted by KCIA when he was in Tokyo. Eugene told me how he drove Kim in his car to meet with Congressmen and Senators in Washington DC. And Eugene would act as the translator during these meetings. When Kim Dae-jung became president, I asked Eugene whether he told President that he e was back in Korea. But Eugene shied away from meeting DJ. Eugene told me, “I’ve done my part. It has come a long way and DJ is now the president. I happy with that do not expect anything further from him. Now I want him to do his job well.”

Eugene told me he first learned about Kwangju Uprising when he read the article written by Bradley Martin on Baltimore Sun. He could not believe what he was reading. He then translated it to Korean and sent copies of it to Korea as rest of the Korean did not know or was misinformed by the military regime on what happened in Kwangju.

But all this activism came at a heavy price for his family. Eugene could never get rid of the guilt that he had for what his family had to go through due to his activism. He thought he could never pay his family back for what has happened. He carried that burden with him, probably until his last breath.

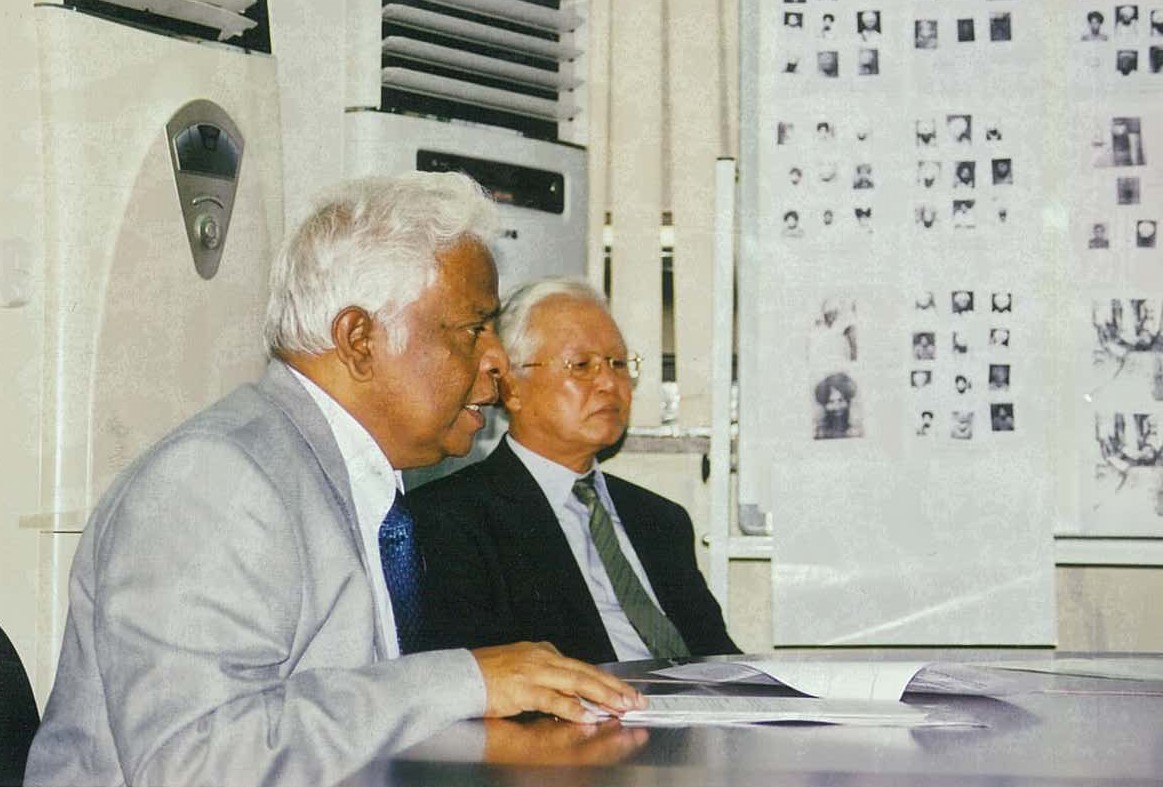

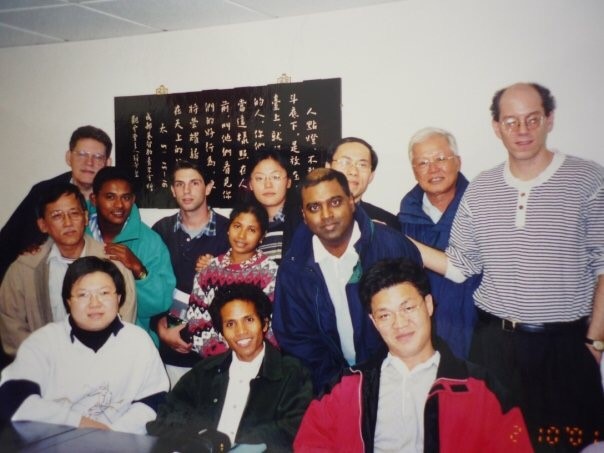

In the mid-90’s he had a key mission–to connect Kwangju to the world and let the world know about what happened in Kwangju in May 1980. with the now-former mayor of Kwangju, Dr Yoon Jang-hyun, a participant and a survivor of Kwangju Uprising Lee Jae-eui, and a few other likeminded people, the Kwangju Citizen’s Solidarity (KCS) was formed in the mid-1990s. It was the KCS that played the pivotal role in linking Kwangju to other social movements in Asia and the rest of the world. Eugene played a key role in organizing the International Youth Camp for Democracy and Human Rights in May 1996, Kwangju in the Eyes of the World Forum in 1997 (when foreign journalists who witnessed and reported Kwangju Uprising in 1980 were invited to Kwangju to tell their stories), and the International Conferences to Declare the Asian Human Rights Charter—a people’s Charter, in 1998. These events inspired the 5.18 Memorial Foundation to actively get involved in connecting to and supporting Asian social and human rights movements and activists.

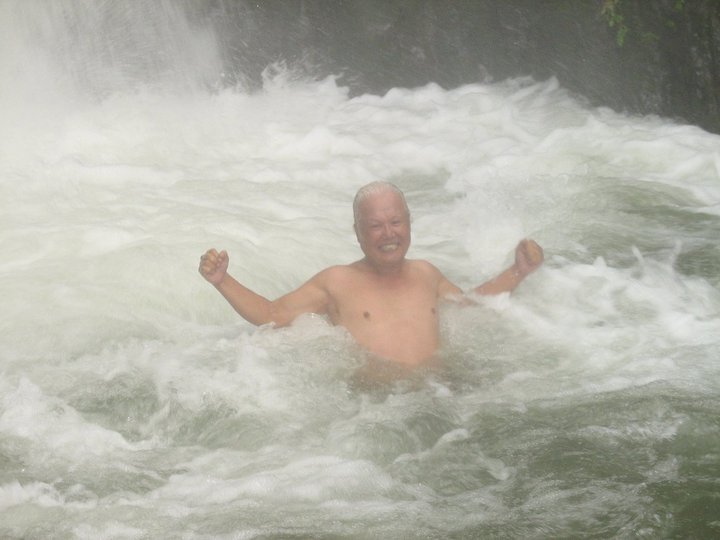

After the unprecedented conference to declare the Asian Human Rights Charter in 1998, Eugene got himself more involved with Asian social movements. He told me in 1998, “Sanjee, I am getting old and before I go if there is anything I can do to help families of victims of human rights violations in Asia, please let me know.” He also said this to Basil Fernando of the Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC). Basil Fernando and I knew what Eugene did best—inspire others who were fighting injustice in Asia with the story of Kwangju, especially the price of the sacrifice of people of Kwangju, their determination to commemorate the uprising in trying circumstances and then to inspire subsequent social events in South Korea which ultimately paved the way to full democracy and the rule of law in South Korea. Eugene first came to Hong Kong in late-1998 to do a presentation for a group of Cambodian lawyers who were being trained on human rights issues. Eugene always spoke with passion and at times he was emotional because he was outraged at what happened in Kwangju in 1980, but he told the Kwangju story in the most compelling manner. Then in early-1999 Basil Fernando asked Eugene whether he would like to go to Cambodia to do a study about its healthcare system. That was Eugene’s introduction to Cambodia, a country that he subsequently made his home. He was also travelling in Thailand, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. He loved this experience—he was connecting to the activists in the region. And, more importantly, it was affordable for him to live in there. He would hitch hike in potato trucks to travel from Cambodia to Laos. He would then rent a moto (scooter) to travel around in the most beautiful sites that tourists never get to see. In 2004, when a victim of torture was assassinated by the police, I called him and asked him where he was and whether he could go to Colombo. He knew the victim, Gerard Perera, and he told me “I am ready to go.” He was in Bangkok and got on a motorcycle-taxi, which he told was the fastest way to go to the airport at that time, and wend to the Dong Muan Airport and used his only savings at that time, about few hundred dollars, to buy the air ticket. Within hours, he was in Colombo with the group of activists helping the family of Gerard and was there until the funeral was over.

In 2010, I introduced two young American men who wanted to go to Laos to Eugene. Eugene accompanied them to Vientiane and next morning found the two young men missing early hours in the morning—they have never returned to motel they were staying. He thought for a while and went directly to the police station to find the two young men in the police holding cell for allegedly being at a place marijuana being smoked. Eugene called me told me, “don’t worry, I will take care of it.” Eventually, he managed to get in touch with a parent of one of the young men and get money wired to Vientiane pay a “fine” to the police and got them out. This was Eugene, who knew what to do at difficult situations and was always available to help.

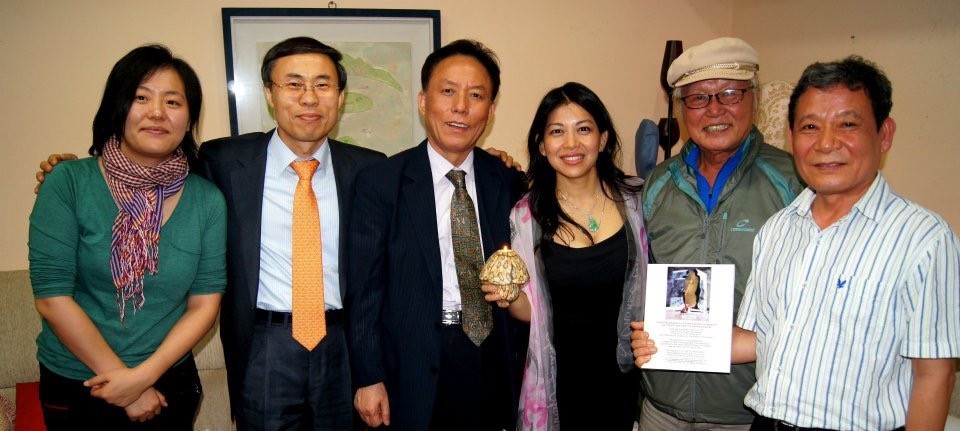

Later in 1999, we Basil gave Eugene another assignment—to go to Sri Lanka and connect to the family members of the disappeared. It was also the year for the first time 5.18 Memorial Foundation invited a small group of families of victims of state-sponsored or enforced disappearances—from Sri Lanka, Indonesia, East Timor and Thailand. Eugene then went to Sri Lanka and connected to Jayanthi Dandeniya (who was later awarded the Kwangju Human Rights Prize), Britto Fernando, Philip Dissanayake and worked towards the mission of building a monument for the disappeared people. This monument, the first of its kind, was inaugurated by the victims’ families in Sri Lanka in February 2000. He traveled to Sri Lanka frequently and even went to civil-war-torn Jaffna during the cease fire period in 2001. He met with activists and scholars in hiding for security reasons like Dr. Rajan Hoole of University Teachers for Human Rights (UTHR). On the day a famous Tamil lawyer and a lawmaker, Neelan Tiruchalvam was assassinated by Tamil Tiger suicide bomber, (Eugene called them Jacket Bombers), Eugene was not too far from the location where he assassination took place. He was loved by everyone he was in touch with. I remember once I was walking with him by a Colombo and someone was shouting from across the street, “Ewugin, Ewugin (how Sri Lankans called him)” and it was a three-wheel (Tuk-Tuk) driver in Colombo who had befriended Eugene. He met with Korean businessmen, diplomats at the Korean Embassy in Colombo and then Tuk Tuk drivers—he connected with all sorts of people.

Eugene hated politics. He loved social movements. He did his part with utmost commitment. But he did not like praise. In fact, he felt very uncomfortable when people were thanking him for what he has done. I have seen numerous occasions he would make a subtle exit from the room when he felt uncomfortable. He just left when he could not stand someone. That was the Eugene I knew. And he dedicated his life to tell the story of the Kwangju Massacre and People’s Uprising to the world. His contribution to Korean democracy is highly underrated or for many an unknown story. But often Eugene too wanted to remain anonymous, to do his duty and then retreat and disappear.

Eugene did not mince his words. He was often blunt—and spoke his mind. Not everybody liked that. Eugene also has this great sense of dignity that even in most needed and helpless situations he would not ask for anyone’s help. His close friends would realize his needs and came to help. But he received such favors with discomfort. He hated being a burden on anyone. I heard that during the years he was living in Kwangju, some days he slept in his car or in telephone booths. He was truly humble and when it came to a task he was bold and fully committed.

Eugene also inspired many young people. He met a lot of young backpackers from around the world travelling in Southeast Asia. He listened to them, talked to them and then shared with them the story of Kwangju and the untold story of decades of human rights violations and failure of democracy in Asia. In 2000 when he travelled with Professor Na Kahn Chae to Sri Lanka and came to have lunch at my parent’s home, he brought along a young university graduate with short hair and wearing glasses. That student was Kim Sooa, being exposed to the world of human rights. Since then Kim Sooa has lived up to the challenge and still carries on that mission passionately.

I last saw him in person in Kwangju in May 2018. I had pictures taken with him, my daughter Aakashi and Dr Yoon at the 5.18 cemetery. We spent many hours over many days together, including a visit to Kim Sang-yoon (김상윤)’s place in Tamyang. Thereafter, we kept in touch over Facebook. During the weeks leading to his passing on, he was helped by his dear friends in Cambodia, including Soe Il Gweon. He returned to Kwangju and spent time with the friends he had there. Professor Na Kahn Chae wrote to me to let me know that friends in Kwangju persuaded him to return to his ex-wife in Baltimore not to Cambodia. Then he first went to Cambodia, packed his belongings and returned to his ex-wife in Baltimore for two nights. On his last day he woke up in the morning, took a shower, sat on a sofa, and passed away peacefully.

Eugene will be missed by his friends. Eugene the unpretentious hero may be not known to many but will live in the hearts of those who have known him and his contribution to Korean democracy. Eugene will also live through the many contributions he has done to the human rights movement in Asia and the generation of young people he has inspired to commit themselves to working to uphold human dignity.

Soh Eugene, Rest in Eternal Peace!

– Sanjeewa Liyanage, Rolle, Switzerland